Patrimônios do Norte - Curatorship and texts for the Brazilian National Heritage Institute, IPHAN

Curatorship and texts

Luciana Carvalho

Marcelo Campos

Thiago da Costa Oliveira (texts in collaboration with Chang Whan, Dominique Tilkin Gallois and Rodrigo Petrella)

Marcelo Campos

Thiago da Costa Oliveira (texts in collaboration with Chang Whan, Dominique Tilkin Gallois and Rodrigo Petrella)

Since 2000, Iphan has taken significant steps in northern Brazil to recognize various forms of Indigenous cultural heritage. This exhibition features cultural assets registered with the Wajãpi (AP), Upper Rio Negro (AM), Enawenê Nawê (MT), and Karajá (TO) peoples. Despite their diverse backgrounds, these groups share a common conceptual affinity regarding the creation of the world. Their mythology often describes humanity's emergence from an underground world to the earthly realm, learning crucial knowledge from beings left behind. Their cosmos is divided into celestial, terrestrial, and aquatic/underground levels, with humanity being distinct from other beings like rivers, mountains, and animals. Indigenous rituals often revisit this rupture, reinforcing a dialogue between beings and the cosmos.

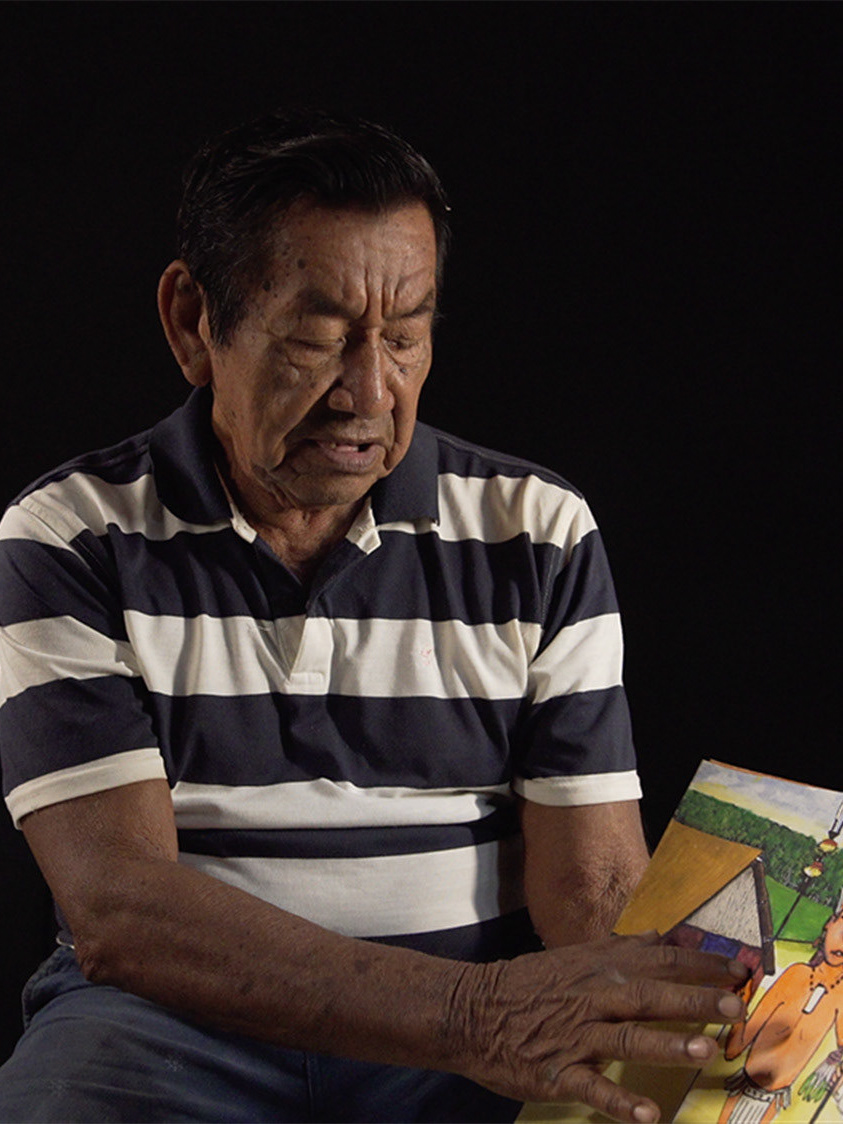

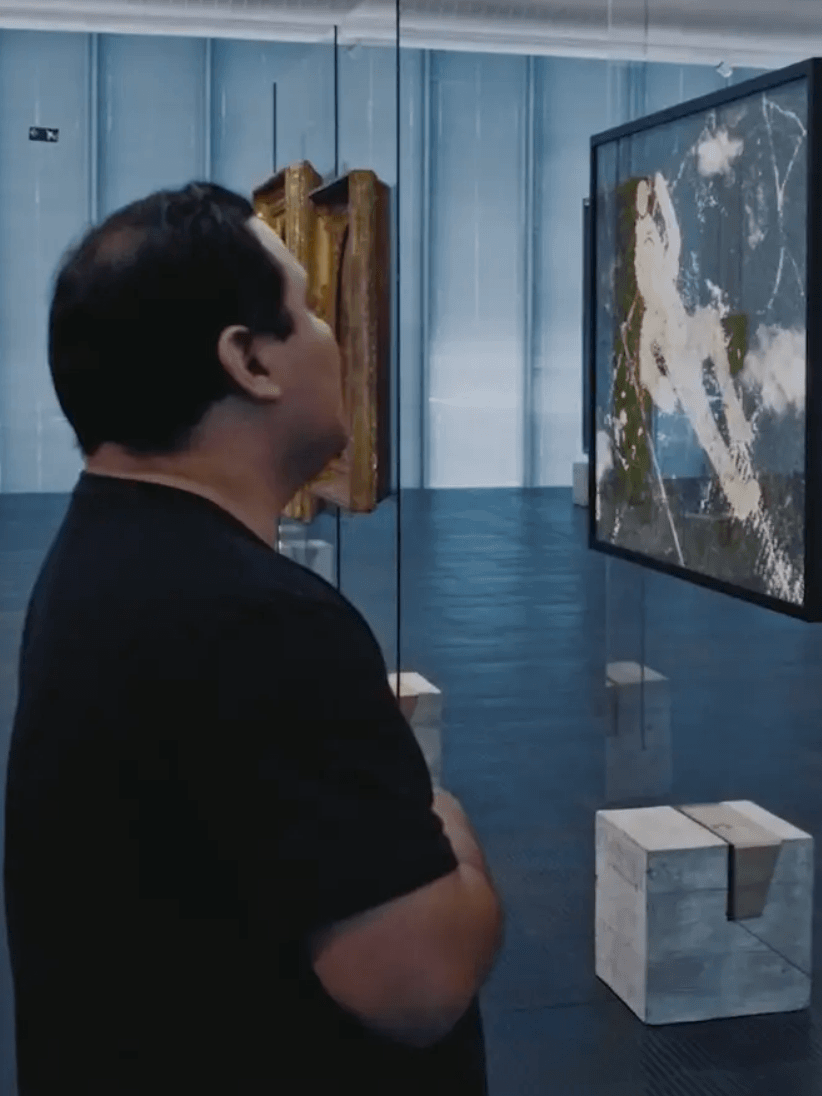

Using this conceptual framework, the exhibition "Patrimônios do Norte" / "Northern Heritage" explored themes like the agricultural and territorial knowledge of the Negro River peoples, the graphic art of the Wajãpi, Karajá pottery, and Enawenê Nawê rituals. It included photographs, ethnographic objects, and audiovisual materials to convey these cultural systems. Photographs depict the contexts of safeguarded cultural manifestations, offering viewers insight into the human and natural landscapes. Ethnographic objects, such as cassava processing implements from the Upper Rio Negro and Karajá ceramics, provide tangible examples. Audiovisual materials, recorded during research, project the voices of Indigenous collaborators who helped document and promote these cultural assets as national heritage.

Picture by Laure Emperarie - IRD - PACTA, Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, 2007

Upper Rio Negro Agricultural System

A small clearing in the woods allows the people of the Upper Rio Negro to maintain a sophisticated agricultural system centered on cassava manioc cultivation. This multiethnic, multilingual system involves 22 Indigenous peoples, speaking Arawak, Eastern Tukano, and Nadehup languages. Their agricultural practices integrate social relations, material culture, territorial management, food processing knowledge, and traditional rules. These practices manage the ecosystem without degradation, linked to broader knowledge of hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Documentaries and safeguard actions by Iphan highlight the transmission of traditional knowledge. The system's registration as Brazilian Cultural Heritage involved partnerships with local and institutional organizations. Key principles include crop diversification and genetic variety sharing. Women maintain gardens and a genetic bank, circulating genetic material through family networks. After two to three years, cultivated areas revert to secondary forests, rich in useful plants. Cassava manioc, toxic in nature, is detoxified using traditional techniques and tools. Kitchens feature graters, juicers, and other objects that reflect practical and aesthetic values. Graphic patterns on these tools carry cultural meanings, referring to animals, plants, myths, and messages from producers.

A view of the Iauaretê Waterfall pictured by Vincent Carelli, 2005

Iauaretê Waterfall: A Sacred Place

The Upper Rio Negro's water regime and relief cause rocks and rapids, called waterfalls, to appear and disappear, supporting the memory of the Indigenous peoples. Cachoeira das Onças, near Iauaretê, São Gabriel da Cachoeira, records mythical episodes about humanity's origin and social and environmental management codes by Kumu, the healers. Historical episodes of wars and alliances shaping the region's sociological conformation are also recorded. These myths and stories are based on traditional knowledge shared by the Arapaso, Bara, Barasana, Desana, Karapanã, Kubeo, Makuna, Miriti-tapuya, Pira-tapuya, Siriano, Tariana, Tukano, Tuyuka, and Wanano. Negotiating these stories' meanings is key to the sociological dynamics of the Negro River peoples.

The registration of Cachoeira das Onças as a Sacred Place involved cultural promotion actions led by Iauaretê's Indigenous associations. Concerned about losing traditional knowledge transmission, Indigenous leaders revived dance malocas and traditional ritual ornaments, previously banned by Salesian missionaries. The film "Iauaretê, Onças Waterfall" documents the dialogue between Indigenous leaders, museums, missionaries, Indigenous and non-Indigenous associations, and the natural elements.

Iphan's safeguard actions were carried out in partnership with the Socio-Environmental Institute (ISA), the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Rio Negro (Foirn), and Iauaretê's Indigenous associations.

Body Painting made with Genipapo, Unidentified Author, IPHAN Archives, n/d,

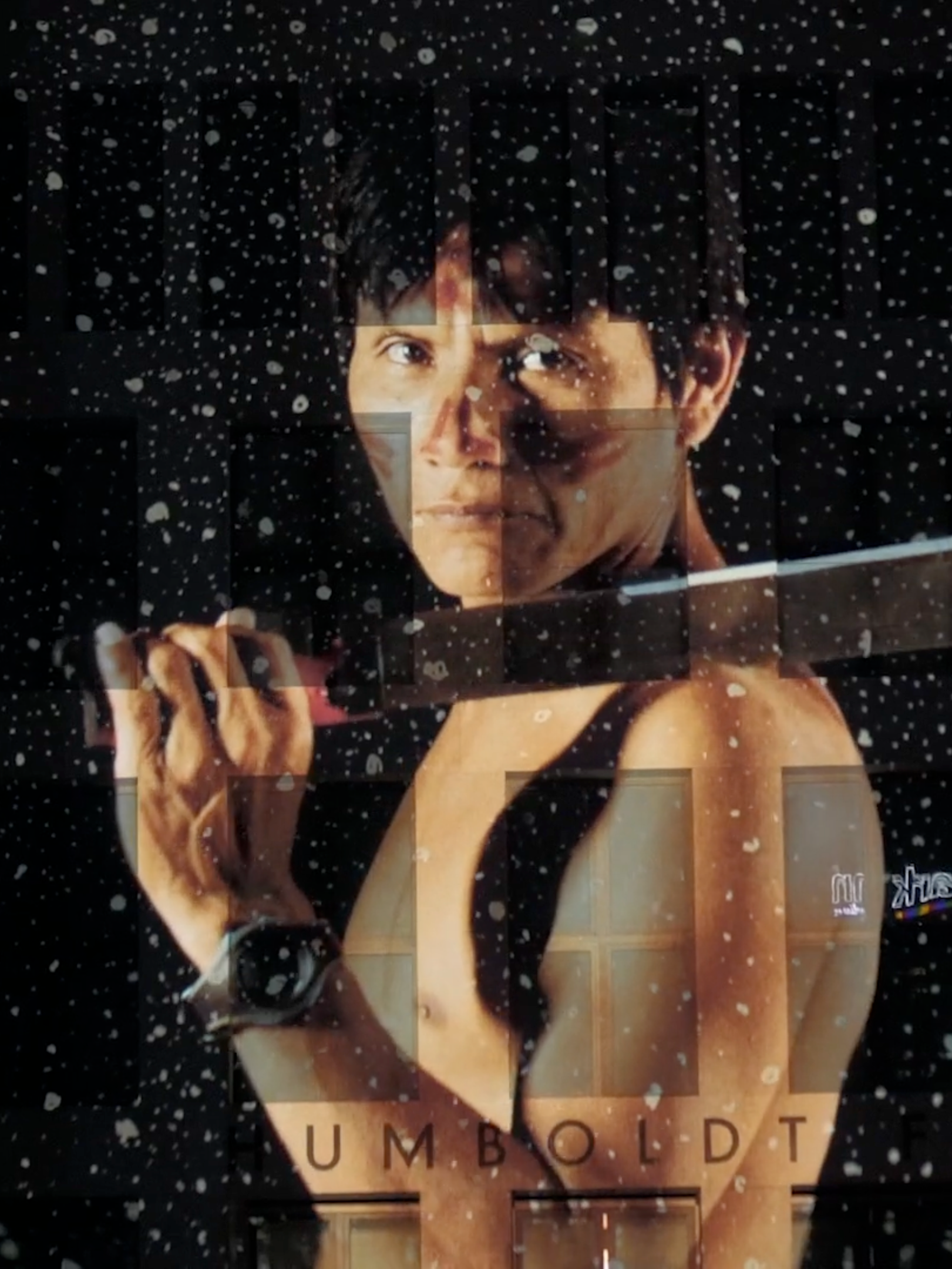

Kusiwa Art: Wajãpi Body Painting and Graphic Art

Kusiwa art, encompassing body care and graphic art knowledge applied by the Wajãpi to the body and other supports, was the first to be recorded in Iphan’s Register of Forms of Expression. This art reflects the presence of other peoples, whose marks the Wajãpi reproduce and with whom they interact daily. The Wajãpi from Amapá, comprising 1,320 people in 92 villages, use Kusiwa graphic language as a form of expression tied to their oral tradition. Stories describe how ancestors discovered colors and graphic forms on animals' bodies, adopting these along with songs and rituals. The ancestors developed stylized drawings of animals like sucuris, jaguars, fish, and butterflies. The iconographic repertoire is historical, dynamic, and changeable, forming a system of internal variations. Each pattern is both similar and diverse, identifiable with tradition. This knowledge is both aesthetic and practical, enabling the Wajãpi to interact with multiple dimensions of the world.

Iphan's safeguard actions, in partnership with the Council of Wajãpi – Apina Villages and the Institute of Research and Indigenous Formation (Iepe), promote the preservation of this art. Wajãpi use urucum, jenipapo juice, and resins for painting, with women painting their husbands and vice versa. They use brushes and stamps, enhancing paintings with necklaces, bead armbands, and feathered adornments. “We know that each pattern has its owners. If misused, their owners may send diseases. We Wajãpi took these patterns from their owners and are now responsible for this knowledge. We devise new compositions using Kusiwaran standards.” (From Kusiwarã [Apina & Iepe, 2009], authored by Wajãpi researchers and teachers with anthropologist Dominique Tilkin Gallois).

Ritxòkò representing aruanás and young women ijadokomã, image by Márcio Ferreira, Museu do Índio, 2011.

Ritxòkò: Artistic and Cosmological Expression of the Karajá People

The Karajá, an Indigenous people in Brazil, have lived in the Araguaia River basin, particularly on Bananal Island, for centuries. They number about 3,500 across 18 villages and speak the Karajá language, part of the Macro-Jê linguistic branch. Karajá culture thrives through collective rituals, festivals, customs, and traditions. This rich cultural heritage is depicted in clay figures called ritxòkò, or "dolls," which illustrate everyday scenes, such as women with children and men in canoes, as well as mythological stories. These ceramic portraits honor the Iny people's cultural practices and traditional ways of life. The Hetohokan festival celebrates the initiation of jyrè (giant otter boys) into adulthood. This ritual includes communal participation and symbolizes the pride of being Iny.

Originally, ritxòkò were small, raw clay figures for girls, known for their bulky bases and absence of arms. The introduction of burning in the production process allowed these figures to evolve into larger, more figurative forms that depict village life scenes, now called wijina bede ritxòkò, or "now-time dolls." Iphan officially registered ritxòkò as Brazilian cultural heritage in January 2012, in collaboration with the Anthropological Museum of the Federal University of Goiás.

Yaokwa series, daw, Photography by Rodrigo Petrella, 2008.

Yaõkwa Ritual of the Enawenê Nawê People

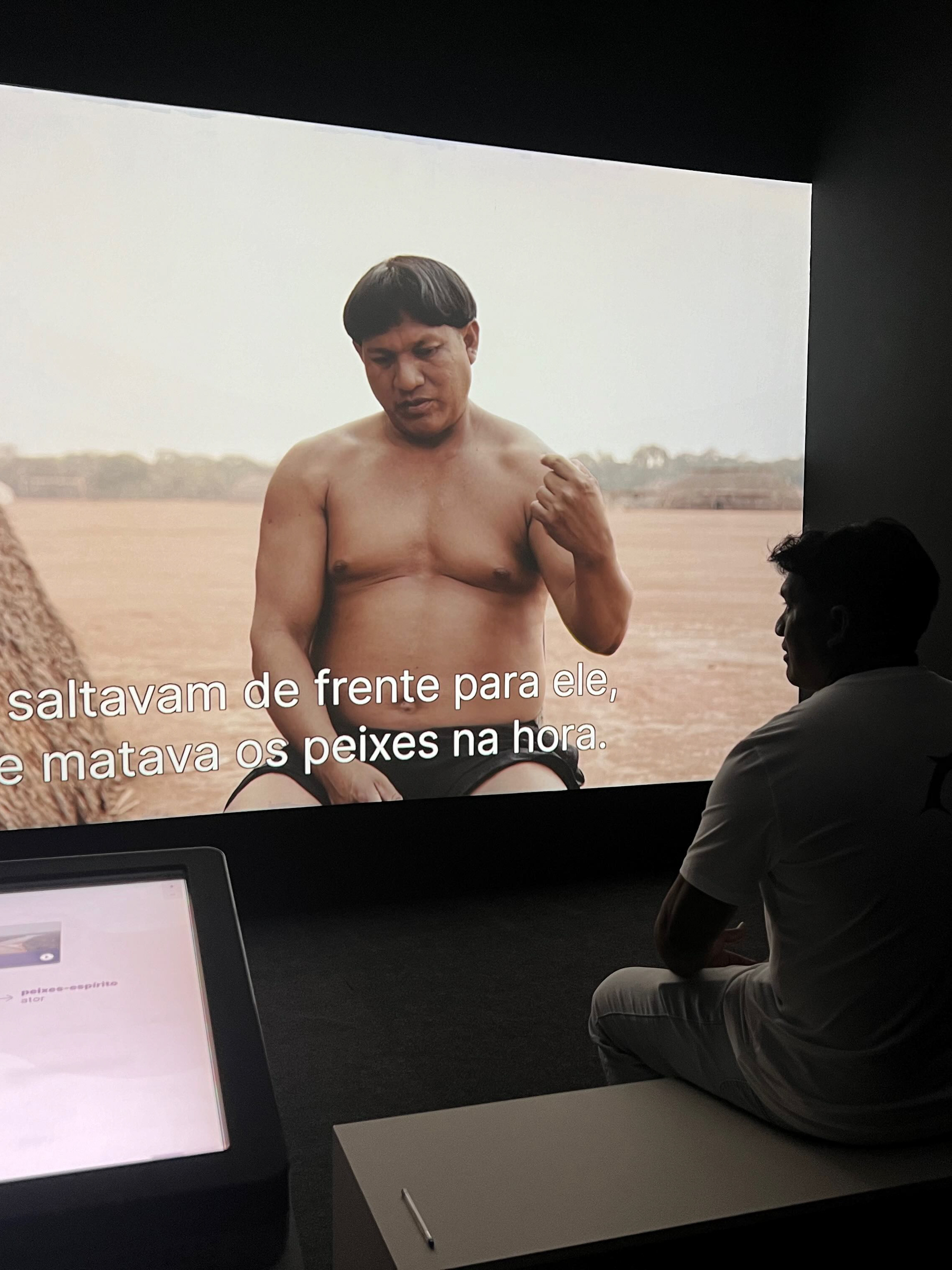

The Yaõkwa is a seven-month ceremony of the Enawenê Nawê, an Arawak-speaking people in northwest Mato Grosso. It occurs during the drought season and aims to appease the Yakairiti, underworld beings with a voracious appetite, through offerings of vegetable salt, fish, and foods from maize and cassava.The Enawenê Nawê divide into two groups: Harikare and Yaõkwa. Harikare prepare the villages, making vegetable salt, gathering firewood, and cleaning. The Yaõkwa fish, using traps in large river dams. After catching the fish, Yaõkwa return, embodying the Yakairiti, and engage in ritual combat with the Harikare. Hostilities cease with a food exchange, and a new phase begins, consuming accumulated food with songs and dances.

The Yaõkwa ritual was registered by Iphan with the Enawenê Nawê and Opan. Rodrigo Petrella's images from 2008 document the ritual and the impacts of deforestation, predatory fishing, and hydroelectric projects on fish availability. The Yaõkwa ritual encompasses knowledge about agriculture, food processing, crafts, and architecture. Its survival depends on preserving the fragile ecosystem, as highlighted in the film "Yaõkwa, A Threatened Heritage," directed by Vincent Carelli.