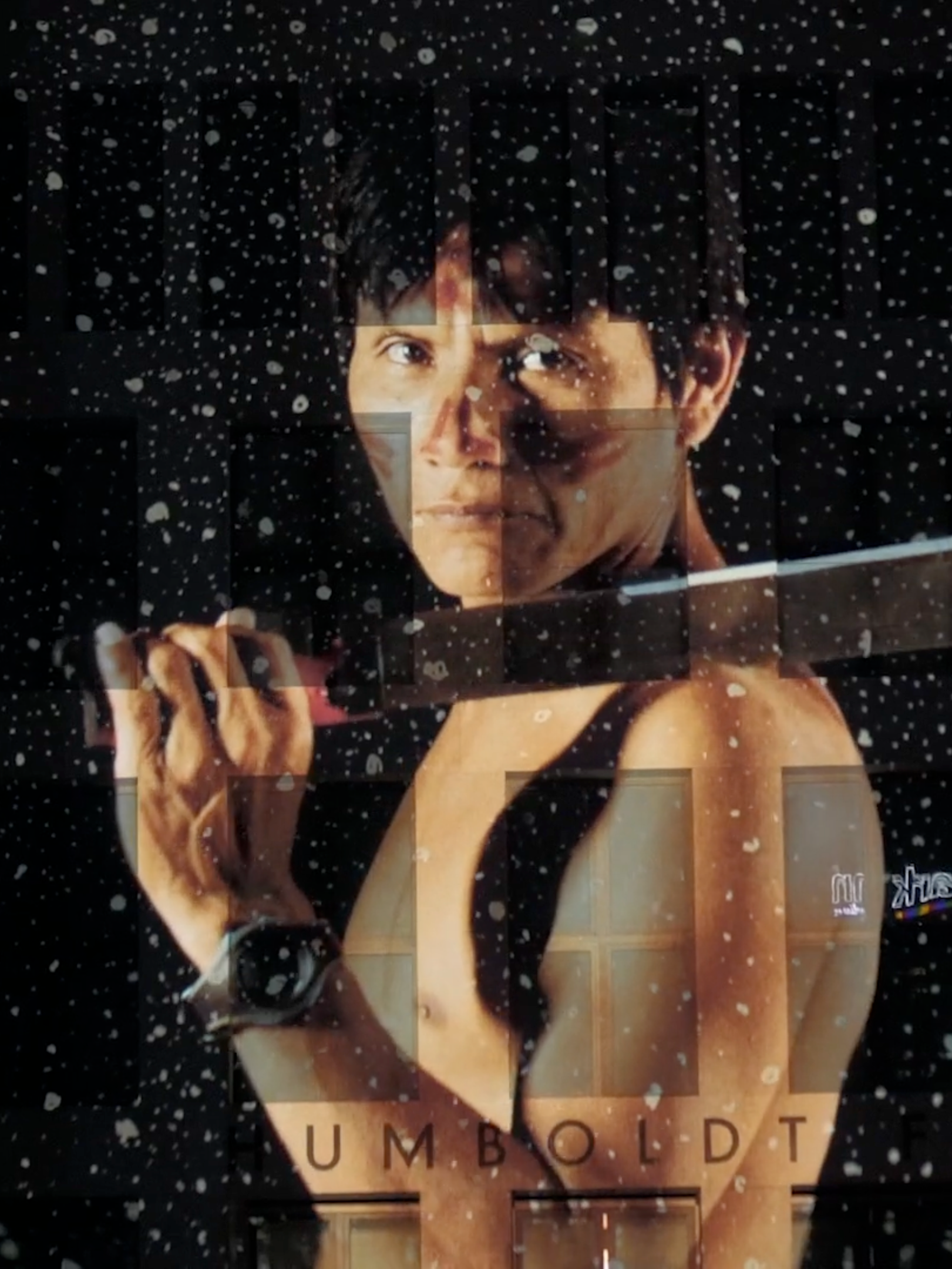

Altamira as a laboratory for the 'development' of Amazonia - Audiovisual production and website creation for the State University of Rio de Janeiro, 2017.

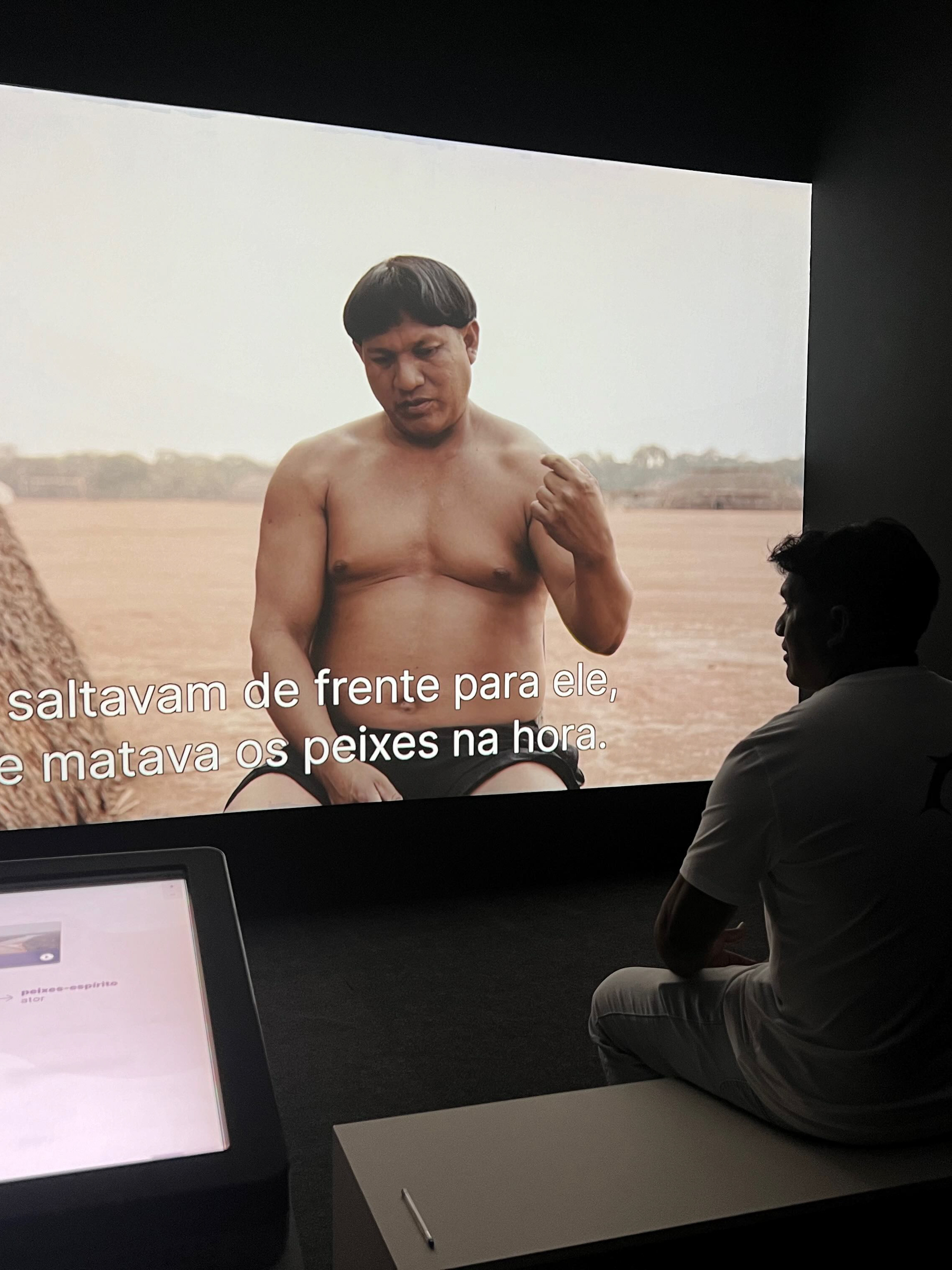

Before being called Altamira, it was known as Tabaquara, a term that can be translated from Tupi as "ex-aldeia" (former village). It was the territory of indigenous peoples such as the Kuruaya, Xipaya, Arara, and Juruna. Before becoming Tabaquara, visited by Prince Adalbert of Prussia and the French naturalist Henri Coudreau in the late 19th century, it was Imperatriz, a Jesuit mission formed by Roque de Hundefund in the mid-17th century.

Altamira was and is a strategically located place in the Xingu and the Amazon as a whole. Its formation occurred late, due to the navigational challenges above the Xingu's volta grande, a cascading section that sometimes took up to 30 days to navigate.

Throughout its history, the city has always been subject to the economic interests that marked each era. It was successively occupied by missionaries, rubber tappers, cat skinners, loggers, farmers, and later by employees of development projects, especially those connected to the construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, and more recently, the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant.

In each of these periods, scars were and continue to be left on the territory and the lives of the region's inhabitants. In the last 50 years, however, the speed of this flow has increased significantly. The city has grown 80 times its size, while the Brazilian population, on average, has grown 20% in the same period.

The speed at which these transformations have been occurring is connected to the erasure of the many individual, familial, and ethnic histories that are part of the occupation of the region. This narrative is shaped by the memories of indigenous people, rubber tappers, cat skinners, loggers, miners, farmers, road builders, and dam workers – and their descendants. They form a complex fabric marked by overlap and, often, conflict.

This series of three videos, created for the State University of Rio de Janeiro and the Federal University of Pará, aims to recover and record these memories.

Thiago da Costa Oliveira, video direction and text

Fabio Nascimento, video direction and cinematography

The Dam

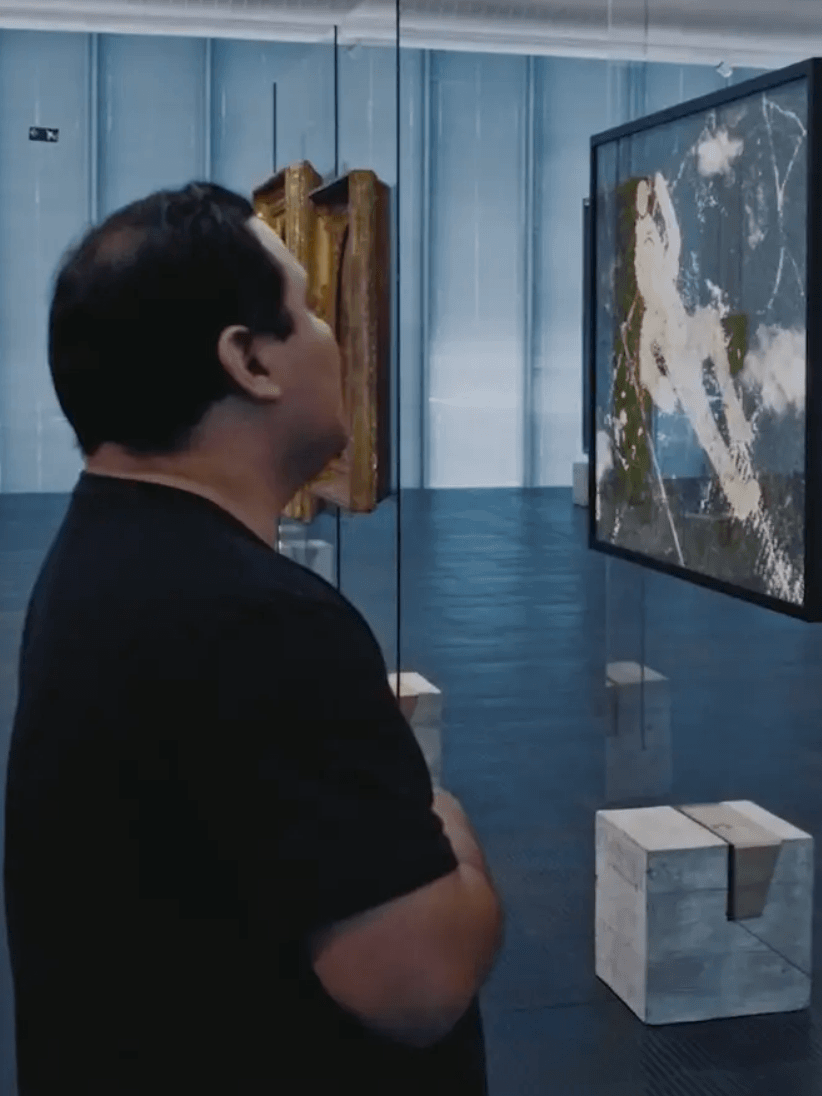

Once an obstacle to the occupation of the middle course of the Xingu River, the "Volta Grande," located about 40 km downstream from Altamira, would be the chosen area for the implementation of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant (UHBM) by the Norte Energia Consortium (CNE). The project began in 2011 and would generate new transformations in the region, deepening conflicts with indigenous communities, the environment, and the population that had settled there in the years leading up to the project.

The figures associated with Belo Monte are alarming. To generate energy, the reservoir created by the damming of the river led to the flooding of 130 km2 of forest around the Volta Grande of the Xingu. Over 450 islands submerged, displacing the residents. The displacement also affected the residents of areas surrounding the streams that encircle the city. In total, over 8 thousand families, about 40 thousand people, and 25% of the municipal area were impacted by the territorial rearrangement set in motion by the construction of the power plant.

The fate of most displaced individuals was the unsanitary Collective Urban Resettlements (RUCs). Hastily constructed by the CNE, these locations did not provide minimum conditions for habitation and imposed an entirely different way of life on the residents. In this process, basic rights related to physical and mental health, financial autonomy, and the way of life of residents in the areas flooded by the dam were

The Highway

When the Pioneers arrived, they didn't know that the land they occupied would be crossed by one of the biggest projects of the military governments in Brazil. The Trans-Amazon Highway, whose construction began in the 1970s, marked a period when the region symbolized the hope for a large and integrated Brazil. The Trans-Amazon represented the revival of economic growth in the region – disconnected from the country's economy since the end of the rubber boom after World War II.

The road brought with it construction workers and farmers from all regions of Brazil, attracted by promises of formal jobs and rural settlements, respectively. The Trans-Amazon triggered profound changes in Altamira, initiating a period of unprecedented population growth. The city effectively became urban during this period. The population quickly rose from about six thousand to 45 thousand people, inaugurating the rapid growth that would continue to the present. With growth came many problems, starting with the road construction, which was never entirely completed.

The construction of the Trans-Amazon consolidated conflicts that are part of the region's history. Conflicts with indigenous people resulted in the contact with numerous previously isolated groups. Conflicts with the environment led to increasingly high rates of deforestation and other forms of forest destruction, such as mining and hunting protected animal species.

In the city, precarious settlement areas emerged over the large streams surrounding Altamira. The "baixões" became associated with marginality, crime, and poverty. The road would only be paved, in the section that cuts through Altamira, with the arrival of a new large-scale project, the construction of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant.

The Pioneer

At the current Km 30 of the Trans-Amazon Highway between Altamira and Brasil Novo, there is a community formed by migrants who moved to the region even before President Emílio Garrastazu Médici decided to open what, in the 1970s, was called the "road of hope."

Seeking refuge from the droughts and epidemics that ravaged the Northeast of the country in the early 20th century, these farmers sought "free" land in the Amazon. They arrived in the region following the encouragement to collect latex from rubber trees but quickly discovered that the lands they expected to be "free" were occupied by Indigenous people everywhere. They also found themselves isolated in an unfamiliar territory. The "pests," the rains, the heat – everything was new. Working the land slowly "Amazonized" them. Today, they are both outsiders and natives. They came from outside and know the forest from within. Their stories are now marked by the affirmation of their role in the social formation of the largest tropical forest on the planet.